Dynagroove® - A Disc Mastering Process

Introduction

Let's look at how RCA promoted Dynagroove to the industry, and to the public in 1963. We'll then look at why they invented Dynagroove, and how it works; and provide the Audio Engineering Society (AES) technical paper written by RCA engineers. Finally, we'll look at the criticism of Dynagroove. RCA quietly abandoned the Dynagroove process by 1970, because it was obsolete, and there were a lot of complaints from reviewers and hi-fi experts. The following pages are part of an RCA industry campaign to sell Dynagroove - to record dealers, and to its own competitors; hopefully to get royalties from the other record companies adopting it. Similar ads were placed in audio magazines like Audio, Hi-fi Stereo Review, and High Fidelity to convince the public to buy RCA and not Columbia, Decca, or EMI. But no other record company adopted it, we'll investigate why.

Why RCA Developed Dynagroove

The ads above sure look great, don't they? Full of confidence, knowing that their new mastering process would take over the world. RCA had learned to be arrogant. The RCA scientists and engineers in Camden and Indianapolis invented Dynagroove because they really thought the idea was theoretically sound, and that it would improve disc recording. I know that Engineers can fall in love with their own inventions (I did that all the time!), but they are not necessarily good Marketeers. RCA Corporate promoted Dynagroove because they believed the scientists and engineers, and was ready to license this new technology, and increase their market share in Records as well.

Instead, there was immediate backlash from other record companies, critics, and the hi-fi gurus. It must have been a disappointing shock to RCA. They were blind-sighted by the reaction. But, this also happened to RCA when they introduced their:

- Audio Compact Cassette system in 1958, large (nothing compact about it) ¼"-tape cassette, cheaply built with bad reviews - Failure. ¹

- Compact 33 RPM 7" single record in 1961, lasted 1+ year - Failure.

- Quadraphonic 8-track tape cartridges called Q8 in 1970 (the original stereo 8-track cartridge was invented in 1964 by Learjet). These cartridges were gone from stores by 1976 - Failure

- Quadradisc CD-4 system in 1972 (joint venture with JVC), disc wear issues - Failure.

- Selectavision CED Capacitive Electronic Disc videodisc system in 1981 - disc wear issues, Philips/Magnavox Laserdisc was better - Failure.

¹To be fair, CBS Labs had a cassette and changer in 1960 that failed, and in 1963 Revere/3M also tried a cassette and failed. CBS and Columbia always were in competition with RCA.

A whole series of marketing blunders and "Edsels" resulted when RCA was too slow to develop, and too stubborn to not end flawed projects. I worked on their SelectaVision VCR in Indianapolis for 4 years, and fortunately they abandoned it before introduction; putting their name on Matsushita [Maht-shoes'-stah] (Panasonic) VHS VCRs. I can tell you that the engineers and employees tried their best to develop what management wanted; but they were well aware of, and frustrated by, RCA's failures since the successes of their 45 rpm big-hole 7" single record, and their Color TV system over a competing Columbia.

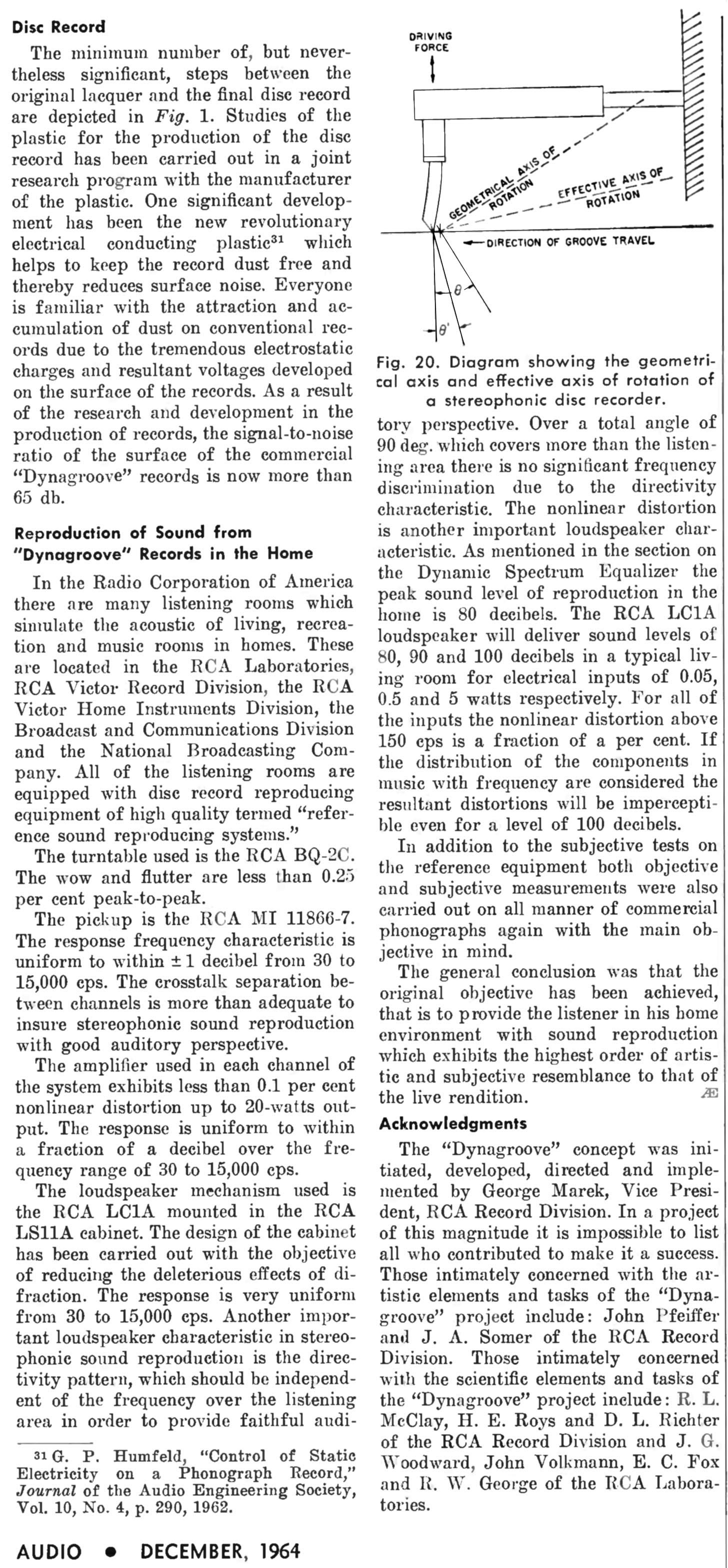

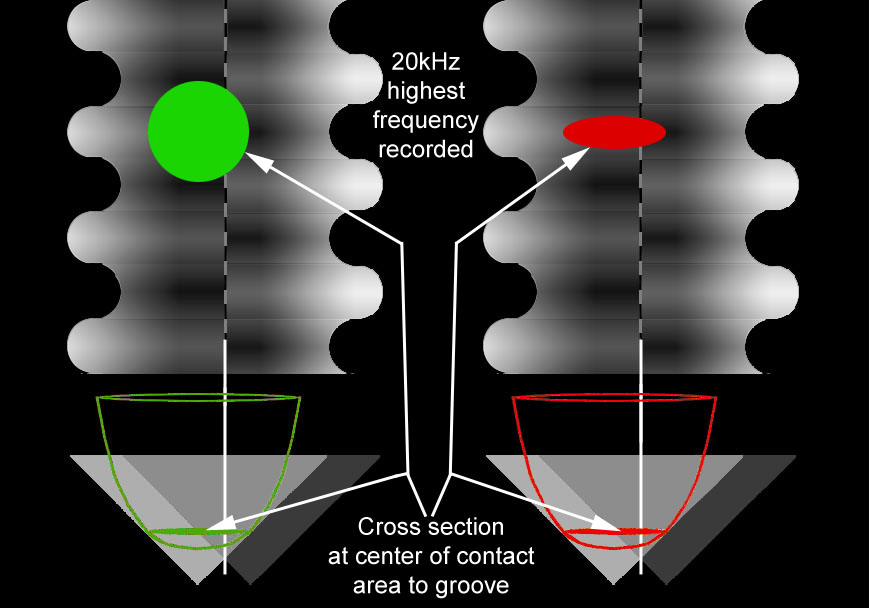

Dynagroove consisted of two major features, and a bunch of minor features that everyone was implementing anyway. The first feature was a distortion-reducing scheme. Master discs are cut with a sharp-edged diamond stylus that is very narrow front-to-back in the groove. When Dynagroove came out, the spherical stylus was all that was available. Being circular in profile, it was as wide in the groove as it was front-to-back in the groove. By 1965, the elliptical stylus was used on high-end cartridges, it tracked the groove without distortion. Shure, a prominent cartridge manufacturer, says that they prefer the term bi-radial rather than elliptical because true elliptical styli are too expensive to make, and bi-radial (i.e. 0.2 mil x 0.9 mil) gives essentially the same benefits as elliptical - better high frequency response and low distortion, with greater record wear.

One advantage of Dynagroove is that it mostly cancels tracing distortion caused by the shape of a spherical stylus (needle) in the groove. The elliptical stylus, which began appearing in 1965 on high-end expensive cartridges by Shure, Empire, Pickering, and Stanton, did not generate this tracing distortion. Dynagroove was basically obsolete 2 years after it was introduced in 1963! It still was valid for lower end hi-fi systems which was the bulk of the market. Those with high-end systems had no choice but to use a spherical stylus cartridge for Dynagroove records. When styli became interchangeable, this was easier.

When you use an elliptical stylus on a Dynagroove record, it actually introduces the inverse of the distortion that is was supposed to eliminate with the Spherical stylus.

Nowadays, we normally use elliptical styli; actually I still use a spherical stylus because it reduces record wear. You really should have a spherical stylus to plug in when listening to Dynagroove records, some cartridges like Shure let you swap the type stylus. The elliptical stylus is best for all other records.

By the way, they invented it because they could, and they thought it would give them a marketing advantage. It was as big a "flop" as the later Dynaflex records! [rim shot]

The diagram at the left shows why the 0.7 mil diameter spherical stylus (GREEN) had trouble tracking high frequency modulations that the cutting stylus easily made. The colored shapes are narrower than the stated dimensions of the styli because we want to show what is going on at the contact area of the groove. The stylus would tend to wear off the sharp turns, and distortion resulted when the stylus couldn't track the sharp turns. This problem gets worse as you get to the end of the record, and so Dynagroove had more compensation at the end.

The 0.7 mil x 0.2 mil diameter elliptical stylus (RED) tracked the high frequency modulations more accurately, with much less distortion, even at the end of the record. Note how the bi-radial stylus can get into the modulated 20kHz better and follow it.

The Dynagroove process uses an analog computer to analyze the signal to the cutting lathe recording stylus, and creates a compensating signal, that when added to the original signal will cancel the distortion to a significant extent. It does this based upon the characteristics of a spherical playback stylus.

What happens when the playback stylus is elliptical? Distortion results! The compensating signal for a spherical stylus does not match the elliptical stylus which has little distortion. The compensating signal is then the distortion heard when playing back. Elliptical styli came out on high-end cartridges only 2 years after Dynagroove was introduced. By 1968, elliptical styli were standard, so Dynagroove distortion cancellation blew up.

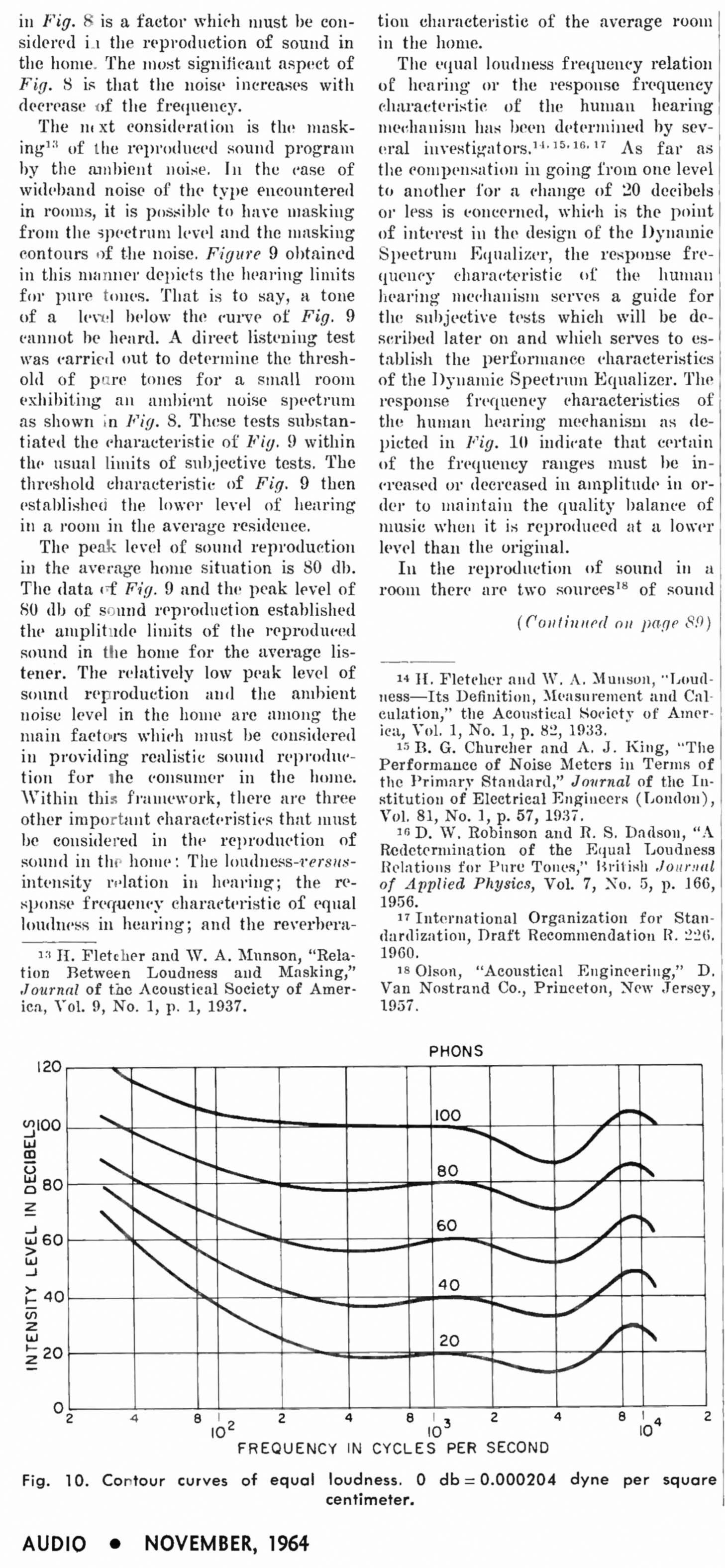

The 2nd major feature was loudness compensation built into the recording. The problem is that most component pre-amplifiers and receivers had this built-in, and the majority of people used it because it made the Bass sound better. Adding this into the record mastering process will double the compensation. Loudness compensation is to compensate the response based upon program level. The human hearing system is less sensitive to bass and to treble at lower volumes. If you listen to music at background levels, you need a lot of bass boost, and treble boost to make the music sound balanced at low levels.

The fact is that Loudness Compensation is not something that is calibrated to specific levels, although it should be. Whether the compensation tracks properly with the volume control depends on the accuracy of the electronic circuit, the efficiency of the speakers, and other factors too. RCA's Dynagroove Loudness Compensation is based upon your listening at 20dB below live performance levels. Who does this? Everyone has their desired sound level depending on the listening conditions and whether you are listening seriously or casually, and depends upon the noise level in the room. There's really no way to know what is correct. Flat response with no compensation is only going to be correct full live listening levels. Compensation using your pre-amp or receiver built-in control is also only correct at one particular lower volume level when using non-Dynagroove records. Compensation with Dynagroove records may be better with your compensation turned off, relaying only on Dynagroove to do it right; but it will only be correct at levels 20dB below live levels.

Dynagroove also involved a number of other improvement to disc processing that were normal and not controversial, other record companies were already doing these without trying to patent or trademark the improvements.

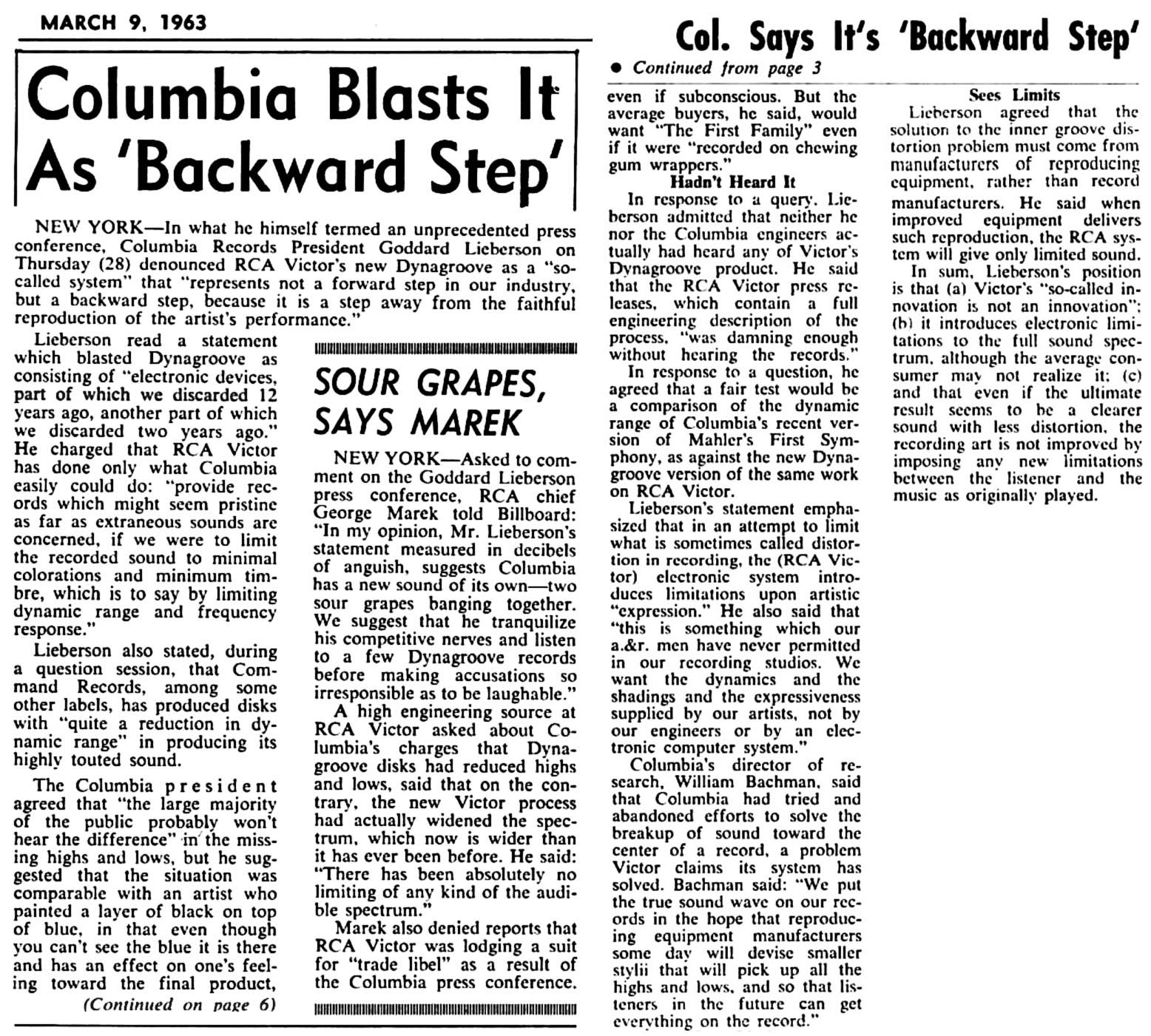

Goddard Lieberson, President of Columbia Records, was an early detractor who said many bad things about Dynagroove, and he had a lot of clout in the record industry. The Billboard magazine article below details his viewpoints. Note that Lieberson had not even heard a Dynagroove record when he made the comments! He based his comments upon an RCA technical description of the Dynagroove process.

In the same issue of Billboard magazine, RCA's George Marek made another statement regarding Dynagroove.

Another influential critic of Dynagroove was J. Gordon Holt, the founder and editor of Stereophile Magazine, until his death. Holt was highly respected, and was one of the first experts to insist that the most important thing about any component in the chain from the microphone to the speakers is how the music sounds. He was not concerned with exotic test equipment numbers, although he found them interesting. Here is a transcript from Stereophile magazine regarding his commentary on the Dynagroove process.

From Stereophile Magazine, June 1, 1963...

The Dynagroove system

RCA Victor terms their Dynagroove process "the most significant advance in the recording art since the introduction of the LP." Significant it may well be, but whether or not it is an advance is another question altogether.

In response to a telephoned query, RCA Victor's recording department filled us in on some details about their new Dynagroove recording process. Allowing for the possibility of some confusion on our part, here is the story we get.

In a nutshell, Dynagroove is a process for correcting automatically certain "inherent" deficiencies in the tracing and the aural balance of disc recordings.

A cutting stylus, having chisel edges, can cut modulations that are smaller than the radius of the playback stylus. In playback, the stylus cannot trace these modulations, but simply bounces over the high spots, causing distortion and rapid disc wear. Dynagroove's computer modifies the signals that would normally create these untraceable modulations, and converts them to modulations that the playback stylus can trace, and which elicit from the pickup signals similar to those it should produce from these signals. This sounds like a good idea, in theory at least.

The second function of Dynagroove is to provide what was described as a sophisticated variety of "automatic loudness compensation," which is supposed to correct for the ear's changes in frequency response at different volume levels. When the orchestra plays softly, the Dynagroove computer boosts bass response. As the orchestra plays more loudly, the bass boost is removed and the upper frequencies are boosted. The adjustments are made almost instantaneously, so that a single bass note in the brief pause between two loud trumpet notes is boosted.

The loudness compensation is evidently intended as a means of restoring some illusion of wide dynamic range to a disc with rather narrow dynamic range on it, but if this is its intent (that is, if we got the story straight), there would seem to be some errors in Victor's reasoning, because Dynagroove's action would tend to reduce the illusion of wide dynamic range.

Manipulating frequency response in accordance with the Fletcher-Munson constant-loudness curves could help to give an impression of more dynamic range than is actually present, by introducing the response changes that the ear would normally exhibit with large changes in volume. But this would call for increasing bass during crescendos and reducing it during soft sections (footnote 1). Dynagroove does just the opposite, although it does boost highs during loud passages, which is consistent with the Fletcher-Munson curves.

We were assured that Dynagroove was not predicated on the limitations of the average low-fi phonograph, but the fact that these compressed Dynagroove discs do fare so well on limited-fi phonographs (we tried them on a boom-box and a portable stereo set) makes us wonder about this. Cutting bass during crescendos does put less demand on phonographs of limited tracking ability and limited power capacity, and boosting bass during every quiet section does help to give the impression of more bass than is actually there. But the workings of this ingenious Dynagroove contraption are plainly audible, and disturbing, when the discs are played on a good system.

One thing is clear, though. The "loudness compensation" is an attempt to offset the subjective effects of extreme volume compression, which in turn is predicated on Victor's contention that, and we quote: "Nobody listens at concert-hall volume." Our comments about that are reserved for the editorial in this issue. If we have misunderstood RCA Victor's intent or reasoning anent Dynagroove, we hope to publish their side of the story in the next "Forum" column.

—J. Gordon Holt, former editor

Footnote 1: The venerable JGH is actually wrong here, as the ear becomes progressively less sensitive to low frequencies as the level drops, thus requiring more bass, not less. But this doesn't affect the gist of his argument. It should be noted that the amount of pre-equalization used by RCA would be wrong at all playback levels except one, and there was no way of record buyers knowing actually what that level was, or of precisely and repeatably obtaining it in their homes.— John Atkinson, current editor

Read more at Stereophile

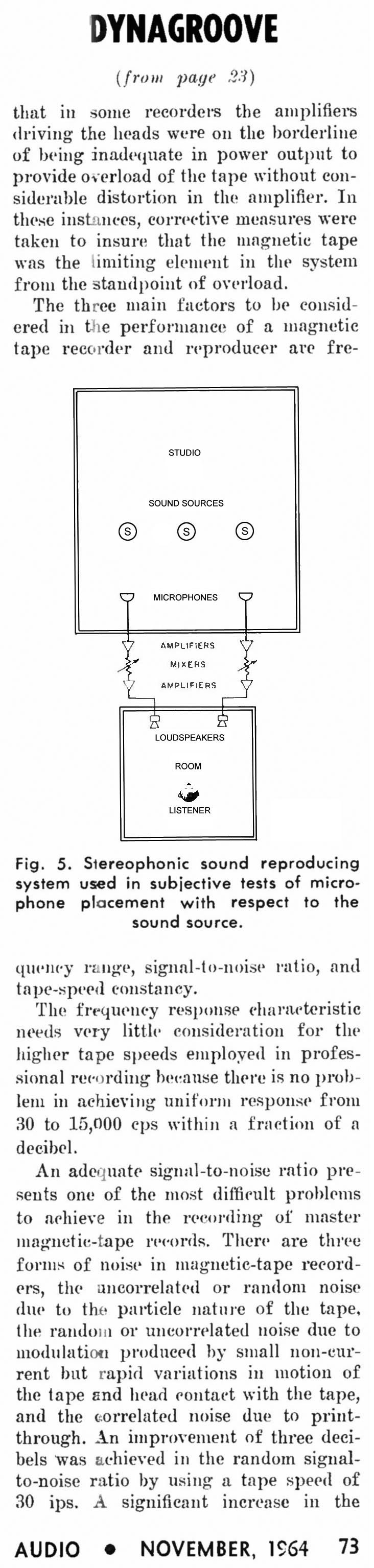

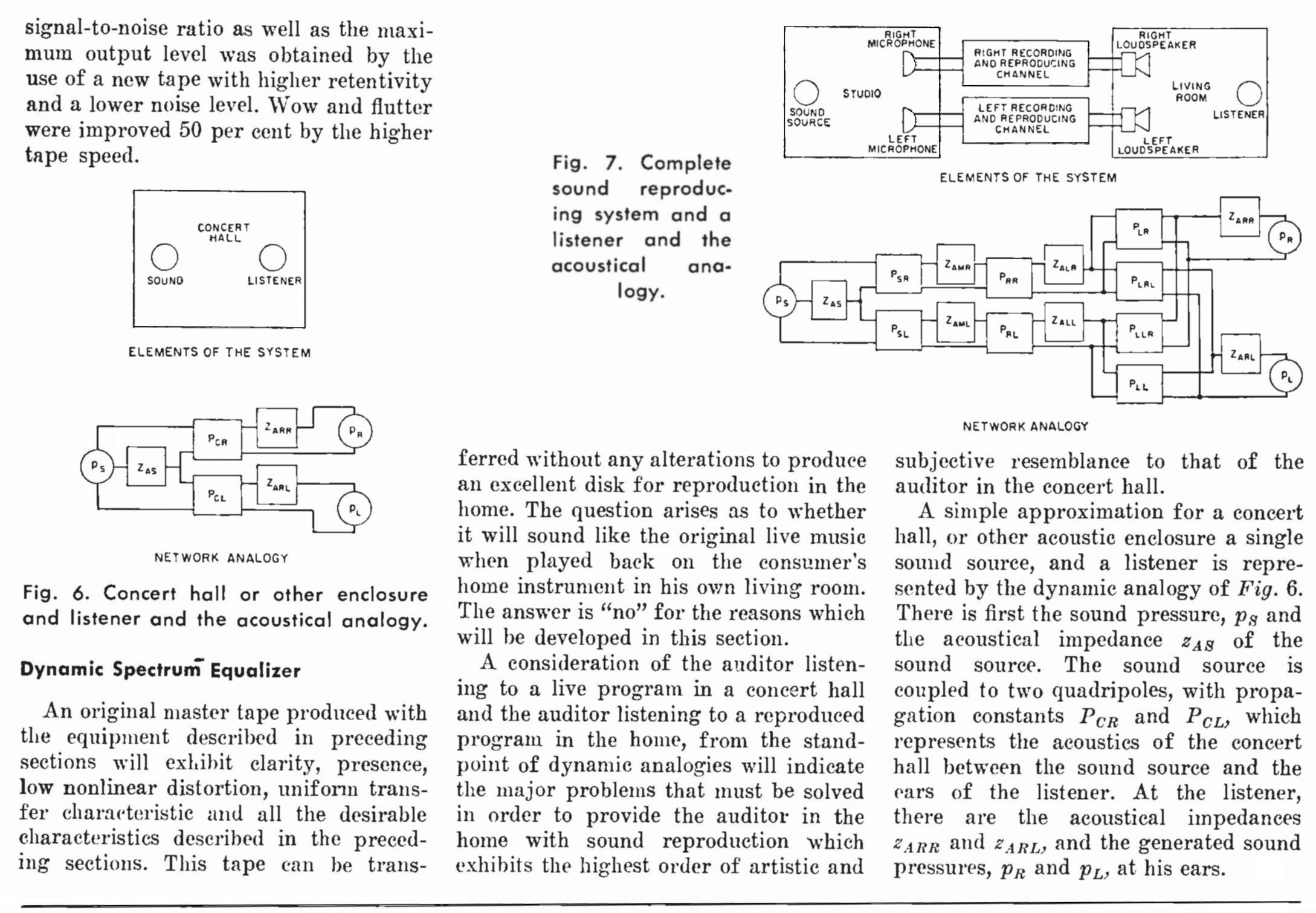

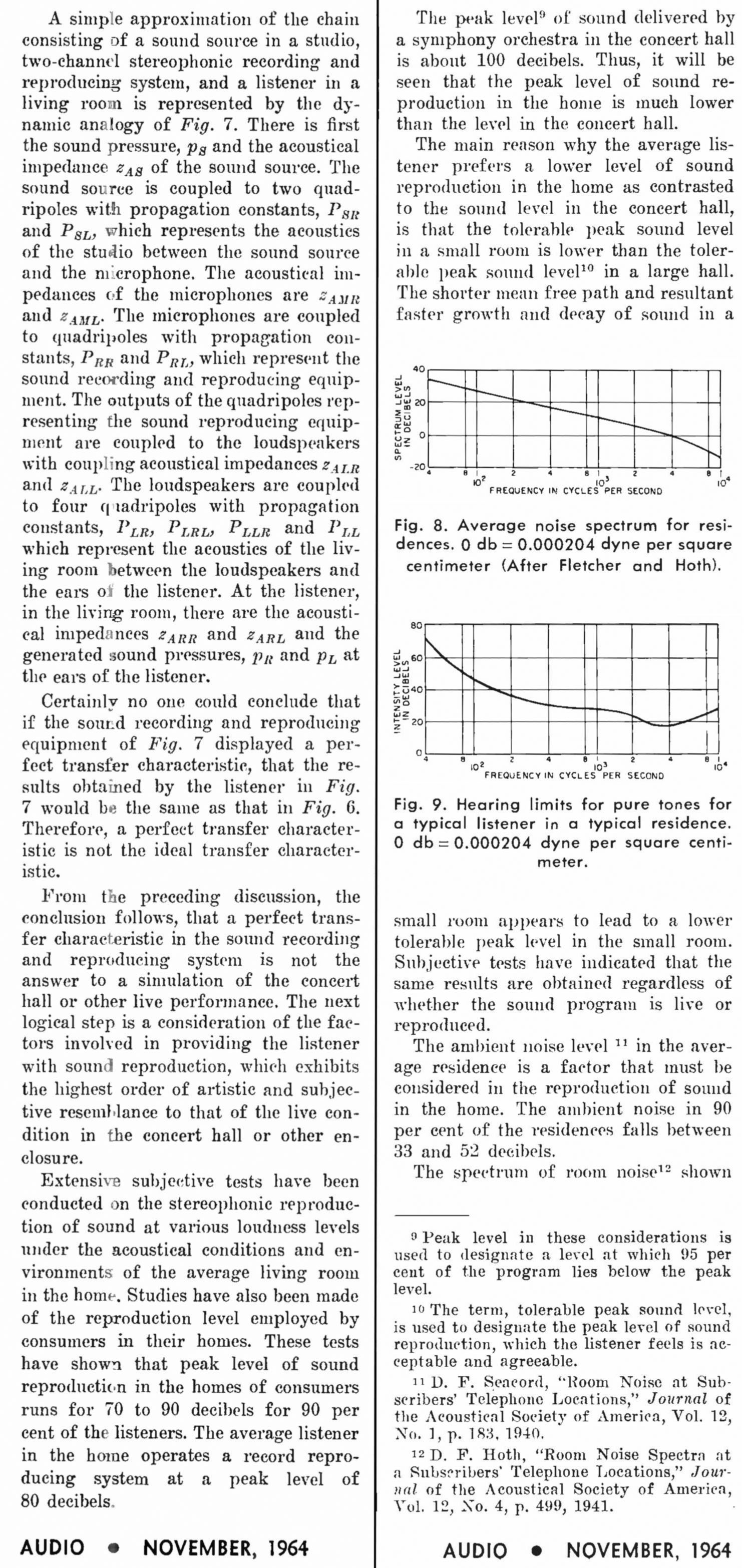

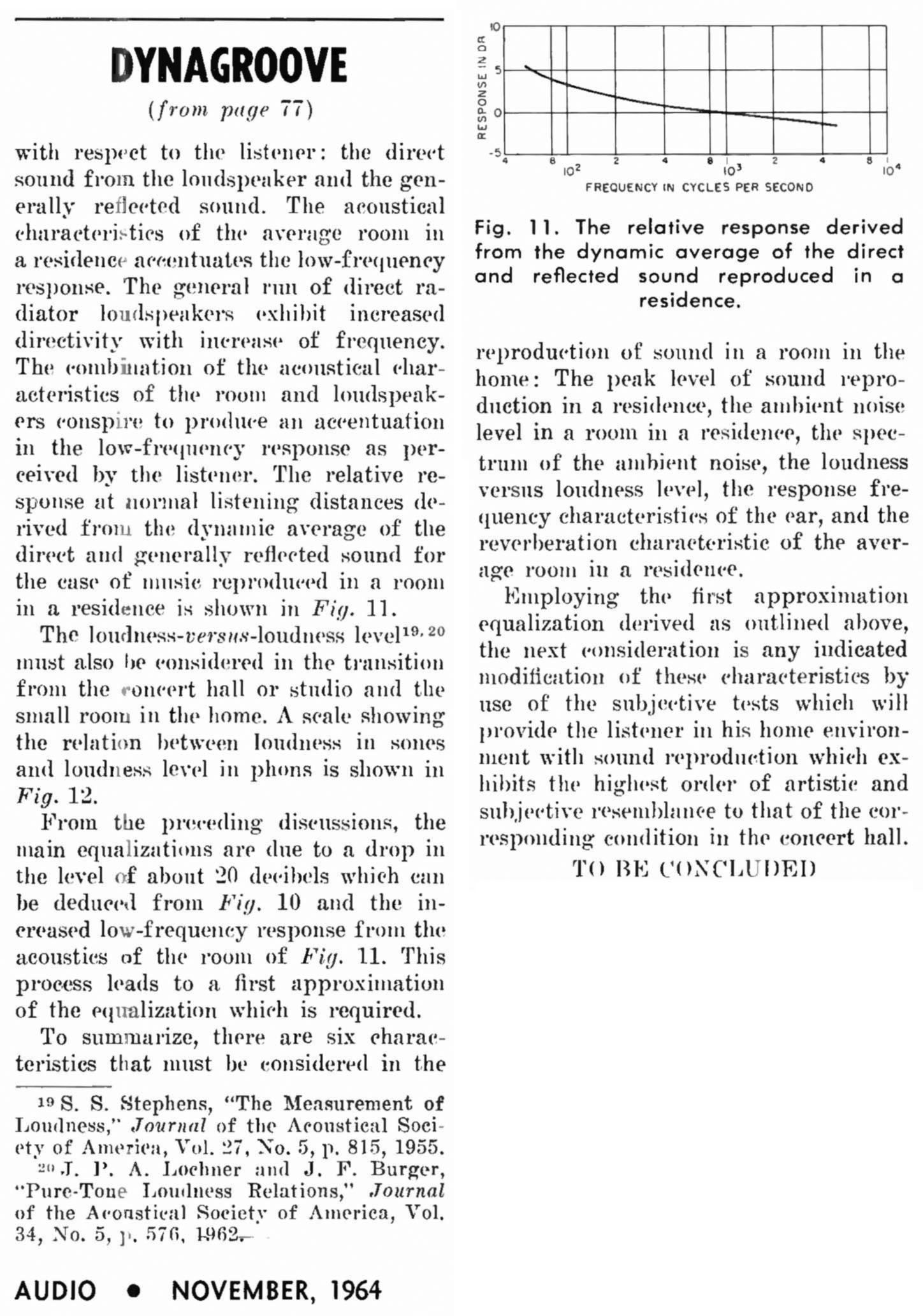

The Pro-Dynagroove argument, below, is from RCA top scientist, Dr. Harry Olson, from his two-part article in the Nov.-Dec. 1964 issues of Audio Magazine. This is very similar to the Audio Engineering Society (AES) paper, also presented in 1964. Olson invented the Ribbon Microphone and the loudspeaker Whizzer Cone.